Francis Joseph McMahon

Francis Joseph McMahon was born on 2 August 1894 at Clough, County Down, the fourth of eight children of Royal Irish Constabulary sergeant Philip McMahon and his wife Catherine (nee Sharpe). Educated at the Newry Christian Brothers School, by 1911 he was living with his family at 8 King Street, Newry, and working as a grocer's apprentice.

McMahon enlisted in the North Irish Horse on 13 October 1914 (No.1308) with his pal Jack McGuigan. He enlisted using the name 'MacMahon', which he retained for the rest of his life.

After training at Antrim, on 17 November 1915 he embarked for France with F Squadron, which was then serving as divisional cavalry to the 33rd Division. Many years later he wrote a memoir describing his experiences:

It was nearly the middle of August 1914. I was on holidays at my uncle's farm. News didn't travel too fast in those days and it was only now people had heard of the war being declared between England and Germany.

It was a real break to holiday here, there was trout fishing, hunting, shooting and the sea was only ½ mile away. And best of all my uncle bred a good quality of horse. I was particularly fond of horses and horse riding. This suited me fine.

When I returned home to my native town which was about 30 miles from Belfast, the town was agog with excitement. It was a garrison town, reservists were being called to the colours and all the young men were eager to enlist. To enlist now was quite the thing, but previous to the war, to enlist was only for corner boys and ne'r do-wells. But now it was "the proper thing to do".

I was educated at a Christian Brothers college where I was taught amongst other subjects, French, German and Gaelic. French was taught by an old French priest and I was keen on learning French and found it very useful.

At that time I was indentured to a firm of wholesale and retail, milling and shipping merchants, a job which I hated, but my father had to pay a premium ... that I would serve 5 years apprenticeship, starting every morning at 7AM, work to 8pm, and on Saturdays until 10pm, I received no pay but had my meals there.

When I returned from holidays I met a friend of mine, Jack [McGuigan], who was a good few years older than me, and whom I knew at school. Jack suggested we should run away to Belfast and enlist in a cavalry regiment. The idea appealed to me so the next morning we boarded a train to Belfast and proceeded to enlist. We wanted to enlist in the Inniskilling Dragoons but they had closed recruiting and were allowed to try another cavalry regiment. Eventually we enlisted [in the North Irish Horse], were sworn in and received our day's pay of 1/- each.

The next day we were issued with a rifle, sword, saddle, blankets and other equipment and were each given a horse, our day was occupied with drawing equipment and all other gear. The next morning Reveille at 5.30am, beds made up, floors swept and then fall in at 6am for physical jerks, dismissed at 6.15am to stables, where one man was detailed to ride one horse and lead 3 for exercise and watering, the remainder of the troop cleaned out the stables, then the exercise party returned at 6.30am and each man started grooming his horse.

We were issued with a curry comb, tail comb, dandy brush, body brush, a sponge (to sponge the horse's nostrils) a cloth and a plaited straw contraption with which you massaged the horse's body after he had been passed as properly groomed by the Troop Sergeant. You were not allowed to use the curry comb on the horse (the curry comb was for cleaning the body brush). If you were caught using the curry comb on the horse you were up before the Troop Officer and were warned by him not to do it again or else. The Sergeant kept warning you to be "careful of that horse, he cost £40, you can get a soldier for 1/-".

After breakfast the recruits were fallen in for riding school. The recruits with their horses formed a large ring in the centre of which stood the riding master, he was a Sergeant with a ram-rod back, a Kaiser William moustache and a fog-horn voice. He taught you the proper way to mount your horse, when you got mounted he gave the order "walk march", after a short time he yelled "trot", the horses were all cavalry trained and on the command "HALT" from the Sergeant, the horses all stopped dead with the result most of the recruits fell over the horses heads. The Sergeant would then threaten those men who had fallen off with disciplinary action, viz "Dismounting without an order".

We continued attending the riding school until the final passing-out test, you got the order "Cross your stirrups over your saddle, fold your arms" and ride your horse over a 4' jump. If you passed the test you were then posted to a troop as a trooper. You were also trained in sword and rifle drill. If you passed your firing test with the rifle you got an extra 6d per day as a marksman.

At the beginning of the recruit's training I had quite a few brushes with the Authorities, but after a few weeks I settled down and began to enjoy the soldiering, the life wasn't bad, you could get a pint of Guinness was 1½d and cigarettes 5 for 1d at the Canteen and you had quite a few good friends and there was always a sing-song in the Canteen from 5.30pm to 10pm. As the regiment was mostly recruited at that time from the north of Ireland, in my troop they were all Protestants with the exception of Jack [McGuigan] and myself. Sunday was a good day for us, we had no church parade, but for the others they hated it. Church parade was all spit and polish, burnished sword scabbard, burnished spurs and a spotless turnout and a lynx eyed inspection by the Sergeant and then after him by the troop officer. The boys used to rouse and say "the next bloody war, I'll be a tyke [taig]". As soon as they returned from Church parade, it was change into stable clothes and off to stables, then grooming and saddle inspection.

Rumours that we were going overseas. We entrained for Dublin, arriving in England we found we were billeted in a small village in Hemel Hempstead, after a spell there we were off to Salisbury Plain, a short stay there and we left for France, just after the battle of Loos. Cavalry weren't required, so we went into the trenches, attached to a Middlesex regiment. The procedure was 1 man to 3 horses and the remainder into the trenches, those left behind had to groom, exercise, feed etc, they had also to mount a guard at night on the horses.

We had various talent amongst us, University students, 2 Australians, one chap from the Canadian North West Mounted police, boilermakers, farm labourers, grocers, you mention it and we had them. ...

The regiment's first six months was on the La Bassee front:

We had a chap with us who had been a solicitor in Shanghai, he got 14 days imprisonment in England for "Ill treating one of His Majesty's chargers", viz galloping his horse on a hard road. On his discharge from prison he reckoned that was the end of his soldiering. He bought a copy of the K.R.R. [King's Rules and Regulations] (which were on sale openly in any paper shop) and studied it. When he would be up on a charge, he would quote K.R.R.'s section so and so in his defence and the charge would invariably be dismissed. He was a real headache to the Sgt. Major, so when there was a request from G.H.Q. for a mounted traffic man, the Sergt Major promptly detailed O'Sullivan for the job. His job was to keep the roads clear for infantry going up the line.

One day in Bethune (a large French Town) a battalion of infantry were going up the line, a French civilian in a cart wanted to break into the column, O'Sullivan tried to stop him, but the French man persisted, so O'Sullivan drew his sword and nearly severed the Frenchman's ear. He was charged with insulting a civilian, he got out of it, saying "he was carrying out his orders".

Shortly after this incident, he was riding through Bethune, where a large number of brass of all regiments were stationed, including the General Commanding the Cavalry Division, O'Sullivan saluted the General's Aide-de-Camp, but the Aide-de-Camp didn't bother acknowledging his salute, so O'Sullivan charged him with "not acknowledging a soldier's salute" and the Aide was reprimanded. Very soon after this incident O'Sullivan was returned to his unit, much to the horror of the Sergeant Major. Apparently by pulling strings by the C.O., O'Sullivan was transferred to England. We never knew what happened to him.

In the trenches I was hit on the head with a piece of shrapnel (there were no steel helmets in the Army at this time 1915), but on account of the shortage of men, a Sergeant just cut the hair around the wound with a jack knife, poured some iodine from a field dressing and declared me fit. About a fortnight after I was again in the trenches and was again slightly wounded in the arm with a piece of shrapnel and again the same treatment.

The regiment spent Christmas in Bethune and then started off by road to outside of Boulogne for Divisional Cavalry training in preparation for the Somme offensive.

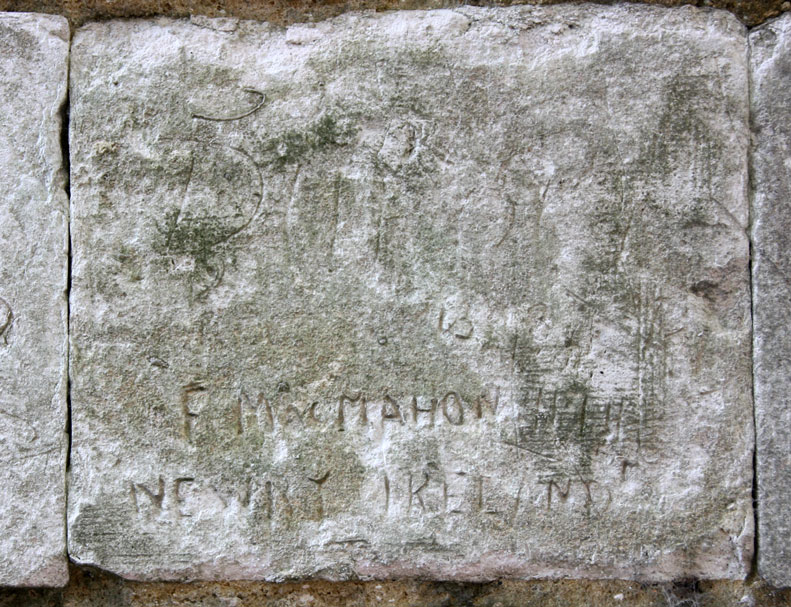

In late 1915 or the first months of 1916, but most probably on 27 November when the squadron was on a 10 mile route march, he carved his name into the soft stone of the church of St Quentin in the town of St Hilaire-Cottes.

In June 1916 F Squadron was re-designated as B Squadron and brought together with C Squadron and the 6th (Inniskilling) Dragoons Service Squadron to form the 2nd North Irish Horse Regiment, serving as corps cavalry to X Corps. The regiment was behind Aveluy Wood at the beginning of the Battle of the Somme and witnessed the attack by the 36th (Ulster) Divison:

This was to be the final break through of the war, guns were moving up day and night, the Artillery were packed wheel to wheel, Cavalry and infantry were there in thousands, we were to be attached to the 36th Infantry Division (North of Ireland). The 36th were to be given the honour of taking the Thiepval wood on 1st July 1916 (in commemoration of the Battle of the Boyne in Ireland).

We moved up behind the 36th Division. The infantry attacked after a terrific bombardment on the German trenches which was supposed to cut the German wire. When the infantry attacked the wire wasn't cut, the Germans were in 20' [deep] dug outs, they simply came out of their dug outs with their machine guns and cut the infantry to pieces, leaving 100s dead and wounded. In the mean time the Germans' artillery ranged in on us, by nightfall we had suffered badly in killed and wounded horses and men.

In August 1917 orders came that the 2nd North Irish Horse Regiment would be dismounted and the men transferred to the infantry. McMahon was one of 70 men given the job of conducting the regiment's horses to Egypt. They embarked from Marseilles on board HMT Bohemian on 25 August. After a month at Alexandria they returned to France, through Italy. McMahon was by then a corporal. He later described this period as follows:

[We] were withdrawn to down near Boulogne, where it was decided to send the horses to Egypt to the Australians.

My knowledge of French came in handy, in doing a few deals with the French.

We entrained the horses for Marseilles (we never knew where we were going until we got there) with an officer [Lieutenant Leader] and some men were put in charge of the horses, we ultimately arrived in Marseilles where an Indian regiment officered by English officers took the horses from us, we hung around Marseilles for 2 weeks, then joined a ship with 850 horses as usual destination unknown.

We set sail with the ship overcrowded with indentured Indians, returning home. We had 2 Japanese destroyers as escort for the ship, conditions were really tough, bad food, grooming horses and cleaning out the manure at night time, it was essential it was done at night, because the manure floated on the sea and it was a real give away for German submarines.

We arrived at Malta but were not allowed ashore, after taking on stores and water we sailed again and finally arrived in Alexandria (Egypt) where the Australians took over the horses. After a short time in Alexandria we boarded a ship (destination unknown). Arriving at some Greek islands we lay up by day in these islands and sailed at night (submarine scare), arrived at Salonika in Greece, then Taranto in Italy, entrained in Taranto, crossed Italy by train, held up at Farenzo [Firenze] whilst the brass discussed using us as reinforcements on the Pavo [Piave River], then back through France to Le Havre, transferred to a famous Irish Infantry regiment, then up into the trenches.

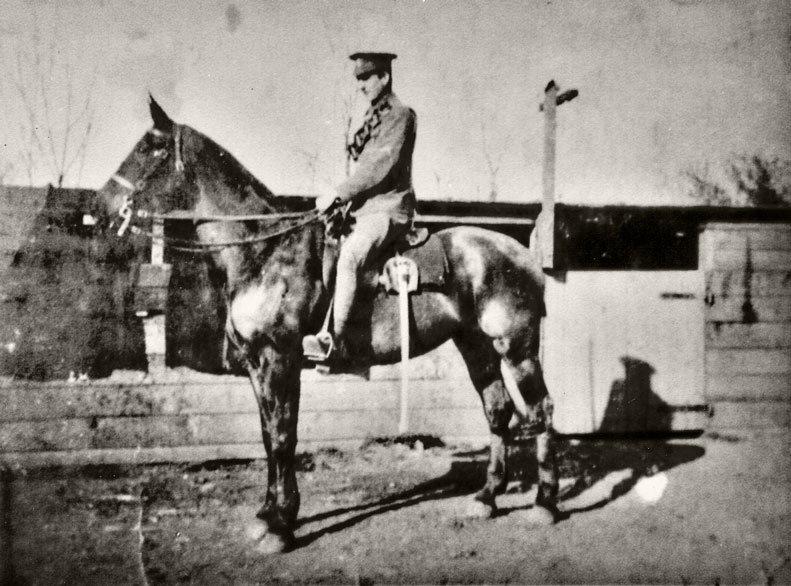

McMahon in Egypt, September 1917. Inset is his sister Josie.

On 5 October 1917 they arrived at the 36th (Ulster) Division Infantry Base Depot at Harfleur for infantry training. After just a few days they were posted to the 9th (Service) Battalion, Royal Irish Fusiliers – renamed the 9th (North Irish Horse) Battalion, joining it in the field at Ruyaulcourt on 12 October. McMahon was issued regimental number 41567 and posted to D Company.

He saw action with the battalion during the Battle of Cambrai in November and December 1917.

On 21 March 1918 the 9th Battalion was at the front near St Quentin.

[We had] intensive training for the capture of St. Quentin, [but] the Germans beat us to it by attacking on the 21st March 1918.

This was the first blow of the German Spring Offensive. Over the next eight days McMahon's battalion made a fighting retreat to just east of Amiens, where the survivors were relieved, having lost the great proportion of their number killed, wounded or captured. McMahon was initially captured with much of his company near Essigny on the second day, but managed to escape. While trying to locate his battalion he attached himself to a French Hotchkiss machine gun unit, but was wounded soon after. According to his account of the time:

I with an advance party of 12 men was captured by the Germans, escaped, joined up with a French unit where we were issued with Hotchkiss M. Guns (we used Hotchkiss machine guns in the British Cavalry). I was shot through the left arm by a bullet, told to make my way towards Paris. Everything was haywire, Armies retreating and demoralised. I was 10 days on the road walking, no medical attention for my arm. Ultimately after a nightmare experience, I was sent from St. Omer to Deauville, then to Harfleur where I was convalescent and marked B.3. Got a job as a clerk to the Commandant of a British staging camp for Americans.

McMahon remained in this job for the duration of the war, rising to the rank of Acting Company Quartermaster Sergeant. He was transferred to Class Z, Army Reserve, on 31 May 1919. In Ireland he found the transition to peacetime difficult:

There wasn’t any jobs I could do offering, [so] I went off to Liverpool, but the unemployment was worse than in Ireland … I had sat for an examination as a Railway clerk in Ireland but had heard no word, [so] I took a job as a barman in Liverpool and after a time I received a telegram informing me I had passed my examination … I returned to Ireland and was posted to a job as the Locomotive Superintendent clerk.

Once back in Ireland, McMahon’s military abilities found an outlet in the war of independence, the civil war and in the cross-border fighting around Newry. He aligned himself with the pro-Treaty forces, as did many Irish soldiers who had returned from the war. However, by the end of 1922 he was forced to leave Ireland. Staying at first with family in Manchester, McMahon recalled the stories Australian soldiers had told him about their country:

During my time in France, I had met many Australians, and liked them. The Australian and Irish soldiers got on well together, they seemed to have much in common, disregard for unnecessary discipline and a devil may care way about them. The Australians and Irish were all volunteers. From personal experience the Australians stopped a complete rout once on the Somme and again in the 1918 retreat, the Irish regiments were always pleased if the Australians were near them in the trenches.

He raised the funds for a passage and left for Australia, arriving in Melbourne on board SS Benalla in January 1923. Here, and later in Sydney, he made a new life, marrying an Australian girl with whom he had three children.

When the Second World War began he joined the Australian Army and served much of the war as a regimental sergeant major in the 16th Garrison Battalion at the prisoner of war camp in Hay, New South Wales.

He died in 19 May 1971 in Canberra, Australia.

More pictures of Frank McMahon and his family can be found here.

I am grateful to Jean Pierre Taverne for his impressive research in tracking down the carvings in St Hilaire-Cottes.